Living Dayton: Past and Present of the Agreement

Introduction

Signed in December 1995, the Dayton Peace Agreement is widely regarded as a diplomatic breakthrough and a long-term structural constraint for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although it brought an immediate end to a 3-year-long devastating conflict, it also created an institutional architecture that continues to influence the country’s political trajectory in complex and somewhat limiting ways (Bose, 2003). 2025 marked its 30th anniversary, making it salient to understand its evolution throughout 3 decades in order to assess Bosnia and Herzegovina’s prospects for peace, democratic consolidation, and EU integration.

After briefly explaining the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, this article will outline the characteristics of the Dayton Agreement, its implications in the present times, and questions about its effects in the future.

The War in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Bosnian war broke out in 1992 in the context of the violent dissolution of Yugoslavia and lasted until 1995. Following the 1991 declarations of independence of Slovenia and Croatia, the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina also announced its independence from Yugoslavia in 1992. The power vacuum left by the collapse of Yugoslavia and conflicting nationalist aspirations exacerbated historical grievances between different ethnicities: while Bosnian Serbs and Croats generally supported their respective neighbouring states, aiming for a territorial annexation to either Serbia or Croatia and opposing a multiethnic Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) population largely promoted the idea of an independent and multiethnic Bosnia and Herzegovina. These different aspirations led to an uncontrolled bloodshed, often carried out by paramilitary nationalist groups.

The war was marked by a siege warfare in multiple Bosnian cities, ethnic cleansing, sexual violence, systemic human rights violations, and mass displacements. In numbers, the war left a death toll of around 100.000, 2 million displaced, and between 20 and 50 thousand women raped (Lampe, 2019; Remembering Srebrenica, 2021). The siege of Sarajevo and the genocide in Srebrenica underscored the urgency of international intervention, especially through the UN peace forces, an effort which has widely been criticised due to its incapacity to protect the local civilian population.

After years of failed diplomatic initiatives and decisive NATO airstrikes, US involvement intensified in 1994-95, laying the groundwork for a negotiated settlement (Daalder, 2000).

The Dayton Agreement: A New Governance…

The peace negotiations took place from 1 to 21 November 1995 in Dayton, Ohio, under the guidance of the US and the presence of the leaders of all three factions: Slobodan Milošević representing the Bosnian Serbs, Franjo Tuđman representing the Bosnian Croats, and Alija Izetbegović representing the Bosniaks (Holbrooke, 1998). Although formally signed in Paris on 14 December 1995, the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina is commonly known as the Dayton Agreement.

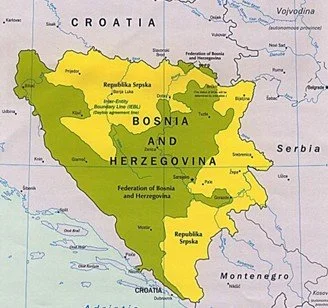

Apart from putting an immediate end to violence, Annexes 2 and 4 of the Dayton Agreement established a new territorial and political system of Bosnia and Herzegovina: the country is now a unified sovereign state composed of two entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, mostly populated by Bosniaks and Croats, and Republika Srpska, inhabited by Serbs, with a complex power-sharing system between the three main ethnicities. Another important introduction was the Office of the High Representative, charged with supervising the implementation of policies (Office of the High Representative, 2025).

Political Map of Bosnia and Herzegovina after Dayton Agreement (Mapsland, 2025)

Politically, the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina has three members elected for a four-year term, representing the three main ethnic groups, with the role of chairman rotating every eight months. The presidency nominates the Chair of the Council of Ministers, then confirmed by the Parliament. The Council of Ministers ought to be multiethnic, just like the bicameral parliament. In the 42-seat House of Representatives, 28 seats are reserved for the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and 14 for Republika Srpska; in the House of Peoples, the respective entity legislatures appoint 5 members for each ethnic group (Pickering, 2025).

Further decentralisation comes at the local level, especially in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is administratively divided into 10 cantons, themselves divided into municipalities (Pickering, 2025). The Republika Srpska is only divided into municipalities, while the district of Brčko, in the northeast of the country, is self-governing, as a result of an unresolved territorial dispute during the Dayton Agreement negotiations.

The international presence remains essential. The Dayton Agreement established the figure of the Office of the High Representative (OHR). With the status of a diplomatic mission and formed by diplomats seconded by governments of the Peace Implementation Council, an international body charged with implementing the Dayton Agreement, the OHR’s main goal is to guarantee a peaceful democracy, overseeing the implementation of civilian aspects of the Agreement, imposing laws and removing officials when necessary (Knaus & Martin, 2003).

While the Dayton Agreement succeeded in ending the war, it also institutionalised wartime territorial and ethnic divisions, shaping Bosnia and Herzegovina’s political system to this day.

…with Lasting Implications

The Dayton Structure continues to profoundly influence Bosnia and Herzegovina’s governance. The rigid consociational system, designed to stabilise post-conflict relations, frequently results in political paralysis, as key decisions require consensus among the three ethnically defined political elites (Belloni, 2009). This has inevitably hindered reforms necessary for economic development, the rule of law, and EU accession.

The intricate institutional system results in an inefficient structure, unable to create true policy change. The agreement created a fragmented governance system, with a ravelled division of power between the three main ethnicities, also leaving smaller ethnic groups such as the Roma without representation. The large number of officials involved in decision-making, owning veto power, results in a slow and ineffective policy-making process, which can hardly handle times of crisis. Despite these inefficiencies, system reform is strongly opposed by nationalist leaders in fear of losing ethnic representation at the national level (Benková, 2016).

The rigid and complex governance structure influences all other aspects of life in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such as the education system with different curricula for each ethnic group, a health system which presents different standards in the two entities, different pension schemes, and an overall stagnating economy.

The protracted international support, under the umbrella of the OHR, third-party aid, and international organizations assistance, highlights once again how the Dayton Agreement was not designed to establish a fully self-sustaining post-conflict political order. Internally, the presence of international actors is also often criticised as foreign interference into national affairs (Hegglin, 2023).

Societal implications are equally significant. Ethnic divisions continue to dominate education, administration, and political representation, reinforcing Dayton-era lines. Such politically crafted divisions influence social division, which, in a vicious cycle difficult to break, further foments nationalist and secessionist political parties. As a result, Bosnia and Herzegovina remains in a situation of persistent political instability and periodic crises. Younger generations increasingly express frustration with the system’s stagnation, yet nationalist political elites benefit from its institutional rigidity (Toal & Dahlman, 2011).

Conclusion

The Dayton Agreement achieved its foundational objective: ending the bloodshed. Yet its longevity raises questions about Bosnia and Herzegovina’s institutional future. Can a post-war-designed constitutional system support modern governance, economic development, and a credible EU path? Or is a more fundamental constitutional overhaul needed?

Proposals of a “Dayton II”, a new constitutional settlement, or incremental reforms surface regularly in academic and policy debates (Bieber, 2010). Any future framework would need to reconcile competing visions of statehood, decentralisation, and identity, and it would require both domestic political will and coherent international engagement, two elements that have often been either absent or mismatched.

As Bosnia and Herzegovina advances slowly toward EU membership and navigates internal political instability, the country stands at a critical juncture. The central question is whether Dayton’s legacy can evolve into a foundation for a more functional, inclusive, and civic-oriented state. This remains unresolved, but it is essential for imagining a stable future for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

References

Belloni, R. (2009). Bosnia: Dayton is Dead! Long Live Dayton! Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 15(3-4), 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537110903372367

Benková, L. (2016). The Dayton Agreement Then and Now. Austria Institut für Europa und Sicherheitspolitik. https://www.aies.at/download/2016/AIES-Fokus-2016-07.pdf

Bieber, F. (2010). Constitutional reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina: preparing for EU accession. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/115432/PB_04_10_Bosnia.pdf

Bose, S. (2003). Bosnia after Dayton: Nationalist Partition and International Intervention. Nationalities Papers, 31(3), 368–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0090599200021097

Daalder, I. H. (2000). Getting to Dayton: The Making of America’s Bosnia Policy. Washington, D.C. : Brookings Institution Press.

Hegglin, O. (2023, December 11). The Dayton Accords 28 years later: The Security Landscape in Bosnia-Herzegovina - Human Security Centre. Human Security Centre. https://www.hscentre.org/europe/dayton-accords-28-years-later-security-landscape-bosnia-herzegovina/

Holbrooke, R. C. (1998). To end a war. Modern Library.

Knaus, G., & Martin, F. (2003). Travails of the European Raj. Journal of Democracy, 14(3), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2003.0053

Lampe, J. R. (2019). Bosnian War. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Bosnian-War

Mapsland. (2025). Large political map of Bosnia and Herzegovina - 1997. Mapsland.com. https://www.mapsland.com/europe/bosnia-and-herzegovina/large-political-map-of-bosnia-and-herzegovina-1997#google_vignette

Office of the High Representative. (2025). OHR: The General Framework Agreement. Ohr.int. https://www.ohr.int/archive/1995-2000/docs/gfa/gfa-home.htm

Pickering, P. (2025, November 20). Bosnia and Herzegovina - Government and society. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina/Government-and-society

Remembering Srebrenica. (2021, June 24). Sexual Violence in Bosnia | Remembering Srebrenica. Remembering Srebrenica. https://srebrenica.org.uk/what-happened/sexual-violence-bosnia

Toal, G., & Dahlman, C. T. (2011). Bosnia remade : ethnic cleansing and its reversal. Oxford University Press.